Nobody knows how old Singapore is, but in the 3th century it was allready mentionned by the Chinese. They referred to it as “island at the end of a peninsula” (Pulau Ujong in Malay). Later, around 1299, it was a village called “Temasek” (Sea Town). According to a legend, during the 14th century, Sang Nila Utama, a Prince from Palembang (the capital of Srivijaya), was out on a hunting trip when he saw an animal that looked like a lion. He founded a city where the animal had been spotted and named it “The Lion City” or Singapura, from the Sanskrit words “simha” (lion) and “pura” (city).

Modern Singapore was founded by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, then the Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen (now Bengkulu). My ancestors worked with him at Fort Marlborough at this time. Raffles landed in Singapore on 28 January 1819. He was looking for a strategic location for a new trading post and saw potential in this swamp-covered island. He helped negotiate a treaty with the local rulers and established Singapore as a free-trade port. The city grew fast in size, population and prosperity and attracted immigrants from China, India, the Malay Archipelago and beyond. In 1822, Raffles implemented the Raffles Town Plan, also known as the Jackson Plan. He also established the first botanical and experimental garden on Government Hill (now Fort Canning Hill) in 1822, which is now on the UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Sir Stamford Raffles was born on his father’s ship in Jamaica in 1781. He lived a penurious childhood and began working at 14. He studied the natural sciences and languages by himself, and his efforts earned him a place at the East India Company’s Penang office. Later he became the Lieutenant-Governor of Java (1811-1815) during this time he did some good and some bad things. After his wife died and Java came under Dutch control he went back to England. A few years later he became the Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen (Bengkulu) (1817-1822). He abolished slavery here and gave people back their rights. He also wrote books about the history, culture, flora, fauna and culture of Indonesia (with illustrations), which my ancestor William Thomas Lewis contributed to.

In 1824, when the Anglo-Dutch treaty was signed, the Dutch formally recognized British control of Singapore. Indonesia, including Bengkulu, came under control of the Dutch. That’s why my ancestors had to choose to stay in Bengkulu and become Dutch or leave and stay English. The ones who left went to Singapore or Malacca with Raffles. He appointed my ancestor William Thomas Lewis to several positions in Melacca and later he became Resident Counsillor of Penang.

Raffles personal life was not easy. His first wife died on Java, her grave is in the Botanic Garden of Bogor. He remarried and had five children. Four of them died in Bengkulu from epidemics, malaria and related diseases. He himself had a brain tumor and went back to London in 1824. He and his family made a stop in Bengkulu to say goodbye. Unfortunately the ship caught fire the night they sailed from Bengkulu and Raffles and his family barely escaped with their lives. All their worldly belongings, including the manuscripts of his next book, were lost. He died very young at age 45 in London. His wife wrote his memoires, in which my ancestor William Thomas was mentioned.

I found a lot of information about my ancestors in the National Gallery of Singapore and British librairy (the East India Company archives) and I’m doing more research about them.

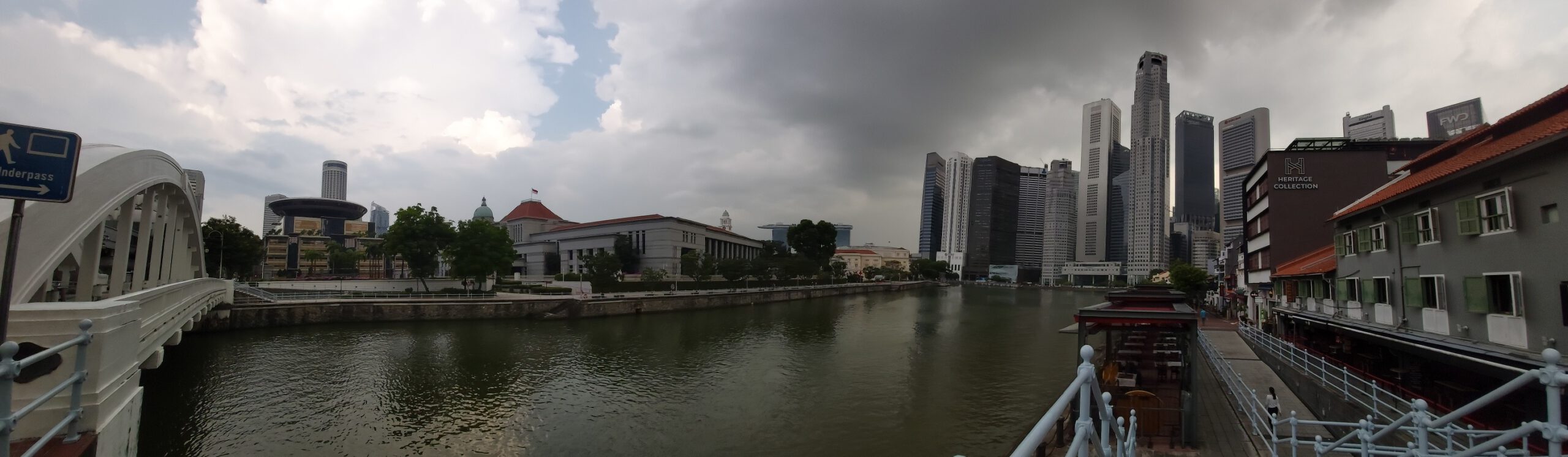

Raffles Landing Site is where Raffles was believed to first set foot on the island in 1819.

The statue is actually a copy of the original dark bronze statue and was placed here in 1972, on the 150th anniversary of Singapore’s founding.

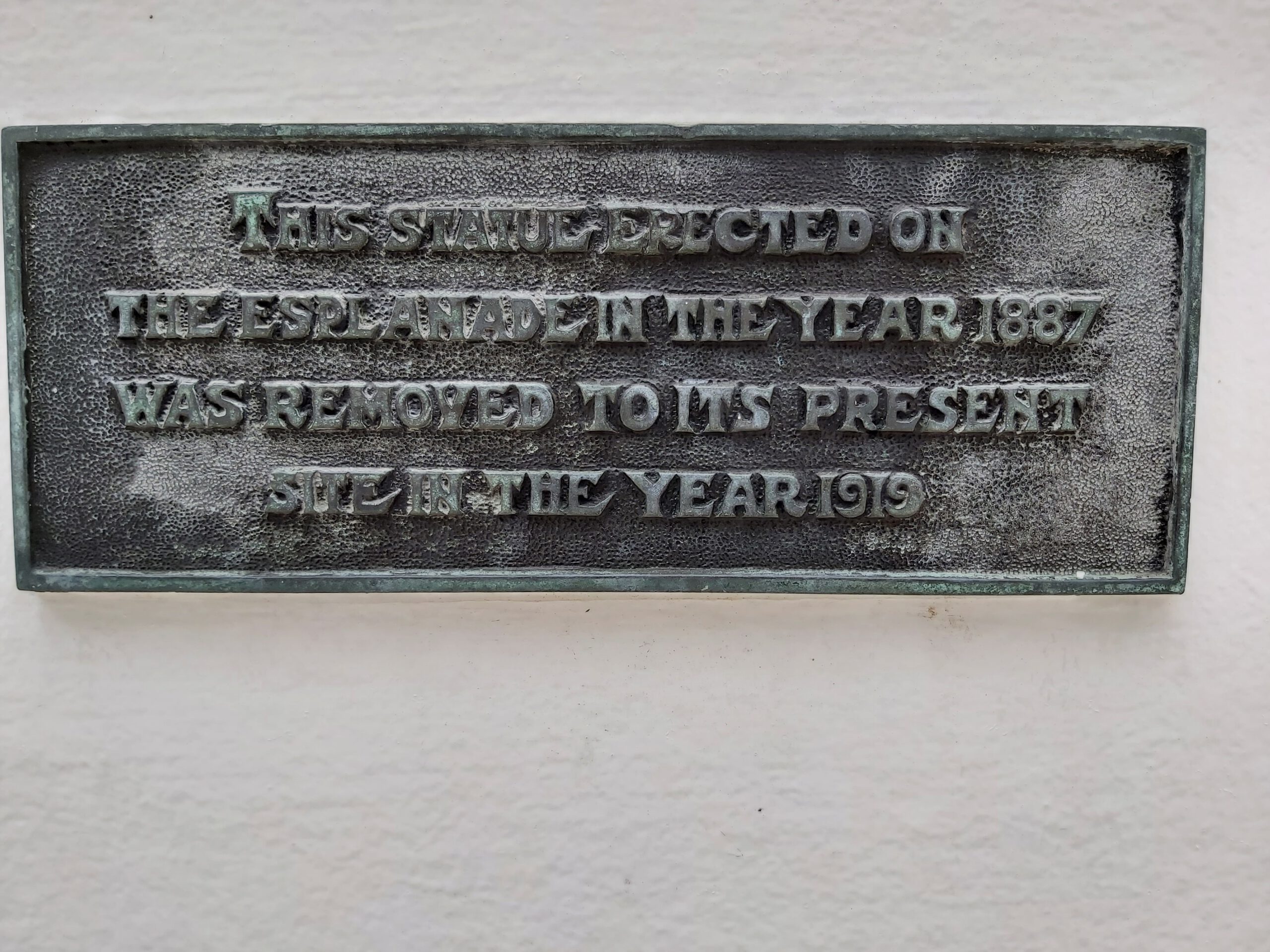

The original statue is nearby, in front of Victoria Memorial Hall at Empress Place. Sculpted by Thomas Woolner and unveiled on Jubilee Day on 27 June 1887. I only found out about this when I was already back in the Netherlands. So the next time I was here I went looking for it and found it inside the area where the formula 1 race was.

Today, the statue is a national icon and remains a symbol of modern Singapore.